Prices and Availability Subject to Change. Please call 800-997-4311 for more Information.

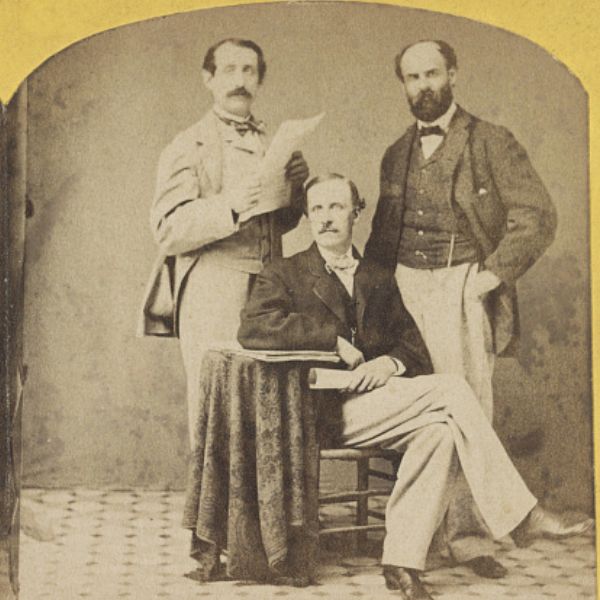

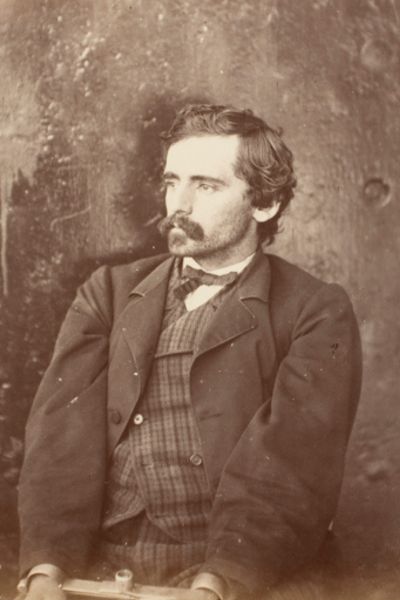

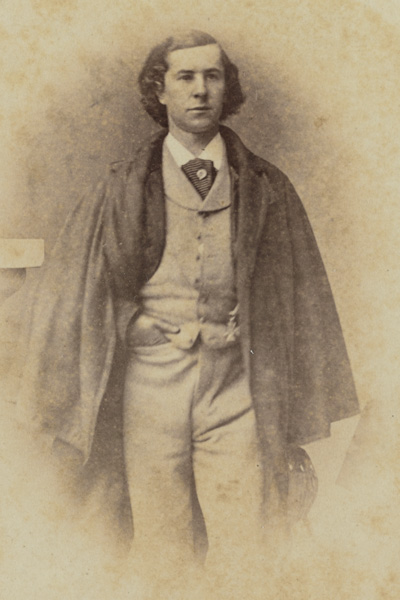

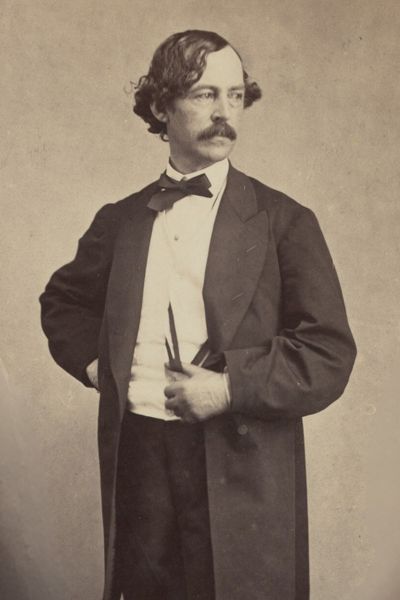

1860s Men's Clothing Guide

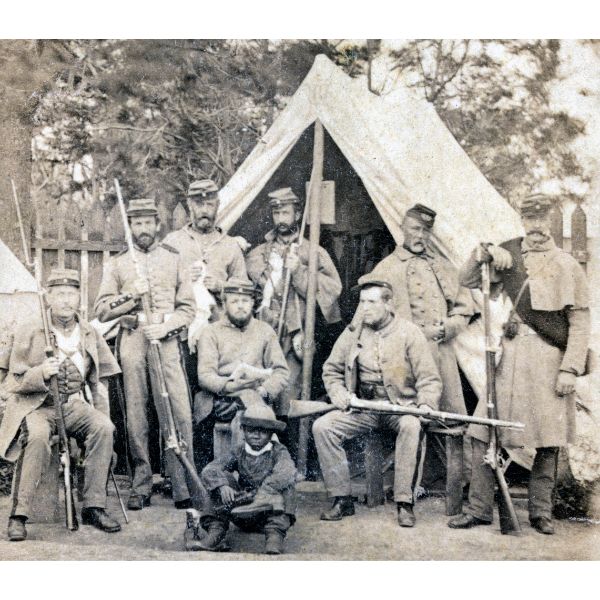

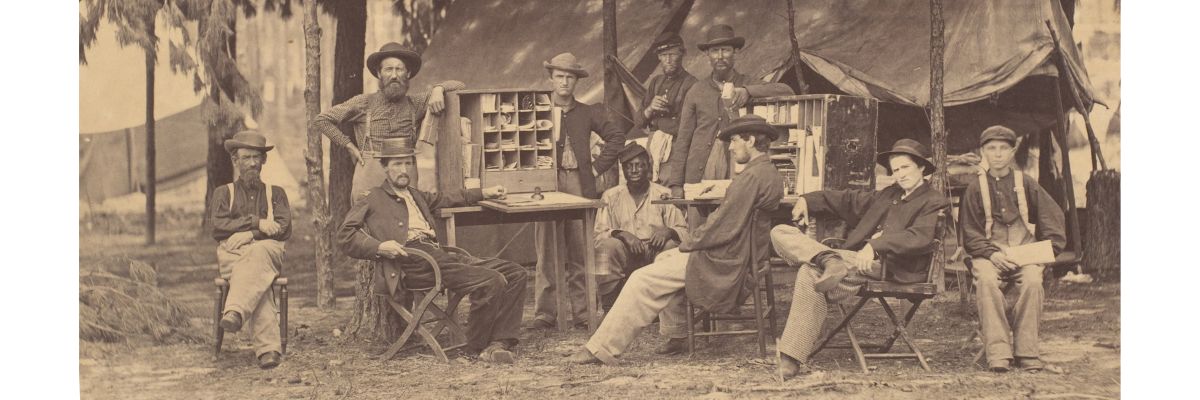

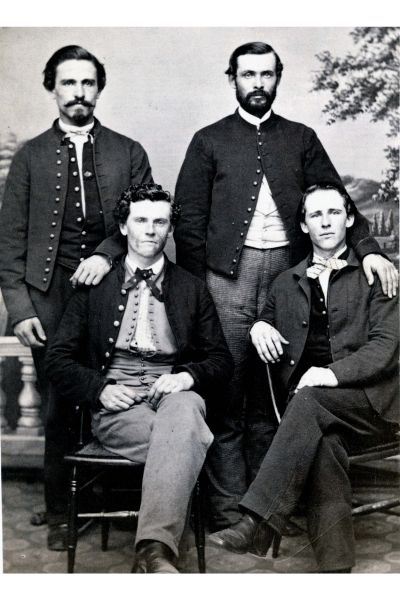

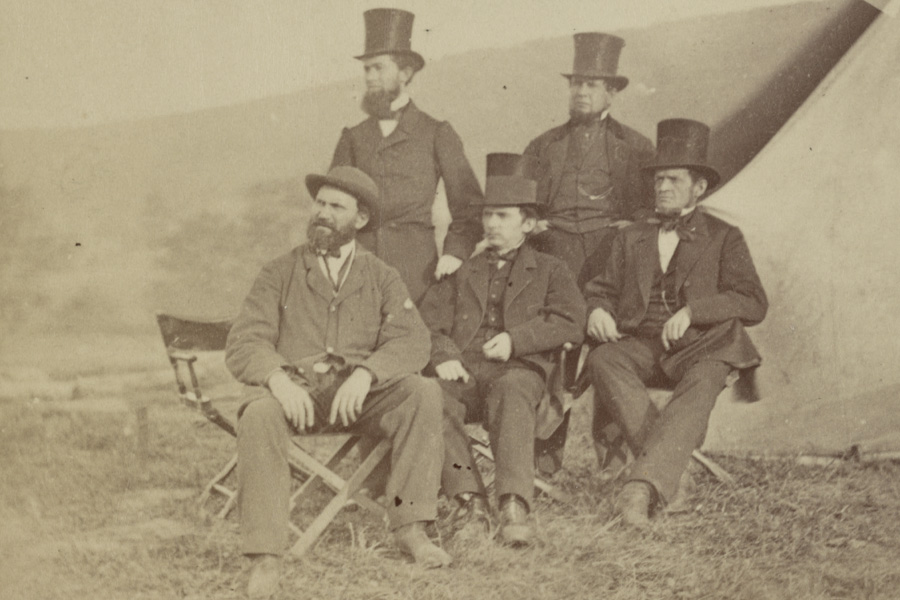

The 1860s marked a transitional period in men's fashion, bridging the mid-Victorian era with the later Victorian styles. This decade saw the beginning of the ready-to-wear era in menswear, largely influenced by the American Civil War and advancements in manufacturing technology. The war significantly impacted fashion trends and textile production, with shortages affecting the entire country, especially the South, which lacked access to Northern imports. The war's end in 1865 saw a shift towards a slimmer silhouette that would define the late Victorian period.

The invention of synthetic dyes in the 1850s, including "mauveine" in 1856, led to a trend for vivid hues in clothing. The death of Prince Albert in 1861 also influenced fashion, as Queen Victoria's mourning dress set a social custom for wearing black after the death of a loved one. This custom spread across all classes, with those who couldn't afford new black clothing often altering and dyeing their existing garments.

Key 1860s Trends

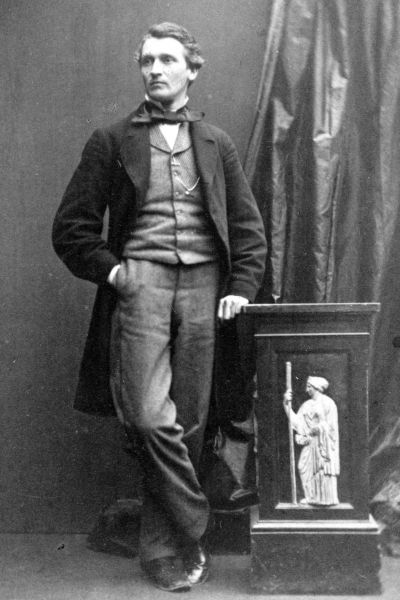

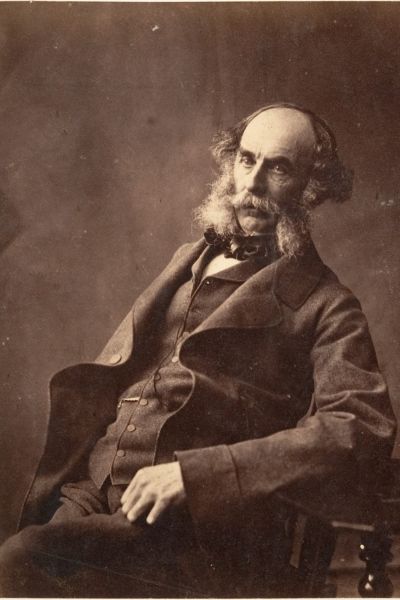

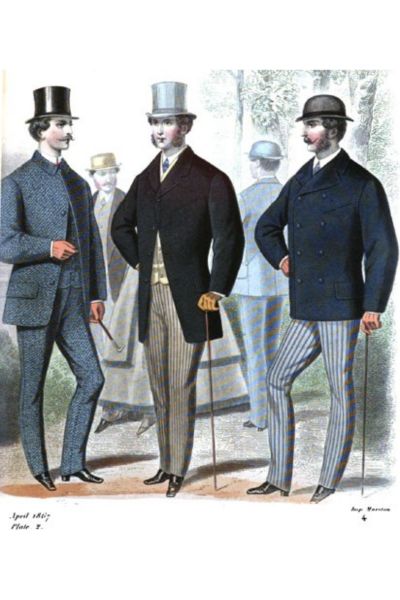

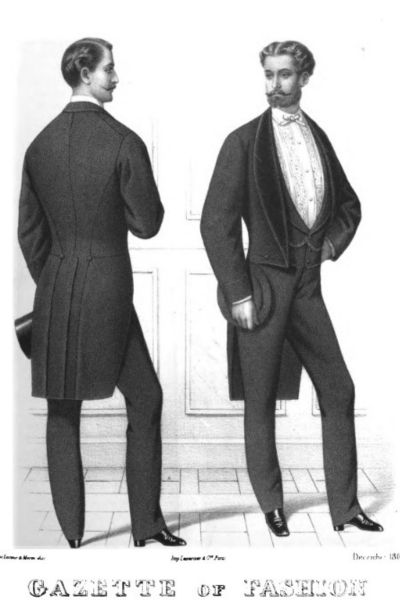

1860s witnessed a significant evolution in men's fashion, marked by a clear divide between the early and latter parts of the decade. The first half of the 1860s largely maintained the boxy, oversized silhouette that had been popular in the late 1850s.

This style was characterized by loosely cut coats with wide lapels, generously cut at the shoulder, and paired with wide-legged trousers. This voluminous look created a strong, masculine silhouette that was favored by gentlemen across social classes.

However, as the decade progressed, a noticeable shift occurred. The latter half of the 1860s saw a gradual transition towards a narrower, taller silhouette. This change was reflected in slimmer-fitting coats with more defined waists, narrower sleeves, and trousers that began to taper more dramatically towards the ankle. This evolving silhouette foreshadowed the sleek, elongated look that would come to define men's fashion in the 1870s and beyond.

A pivotal factor in this fashion evolution was the increasing accessibility of ready-to-wear clothing. This accessibility was largely due to significant advancements in sewing machine technology, which allowed for faster and more efficient garment production. The Singer Company, founded by Isaac Singer in the 1850s, had become the world's largest manufacturer of sewing machines by 1860, revolutionizing the clothing industry. These machines could produce garments in half the time it took to create them by hand, leading to the establishment of factories that mass-produced men's shirts, underwear, and other clothing items.

Another crucial development was the standardization of sizing in men's clothing, a direct result of the American Civil War. The need to quickly produce large quantities of uniforms for soldiers led to the collection of extensive measurement data.

This data was subsequently used by clothing manufacturers to develop general menswear fit and size ranges, making it easier to produce ready-to-wear garments that would fit a broad range of customers.

This democratization of fashion had far-reaching effects. It allowed for greater variety in men's clothing, as manufacturers could now produce a wider range of styles more quickly and affordably. It also increased accessibility, making fashionable clothing available to a broader segment of society. Men who previously might have owned only one or two suits could now afford to have a more varied wardrobe, allowing them to dress appropriately for different occasions.

Moreover, this shift towards ready-to-wear clothing began to blur some of the stark visual distinctions between social classes that had been more pronounced in earlier decades. While quality and fabric choices still signified wealth and status, the overall silhouette and style of clothing became more uniform across class lines.

These changes in production and accessibility, combined with the evolving aesthetics of the decade, set the stage for the rapid fashion changes that would characterize the latter part of the Victorian era. The 1860s thus stand as a pivotal decade in men's fashion history, bridging the more rigid styles of the mid-19th century with the increasingly varied and rapidly changing fashions of the late 19th and early 20th centuries.

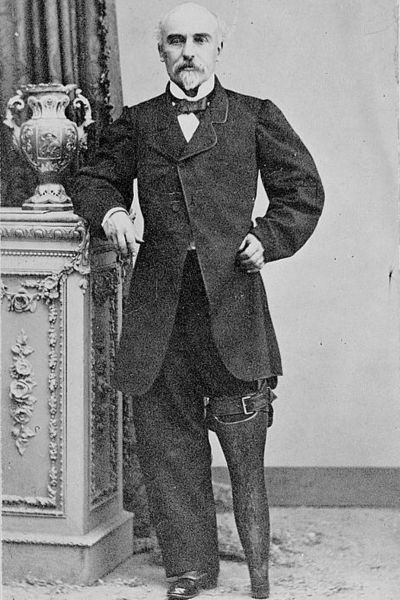

Frock Coats

The frock coat remained a staple for formal daywear, though it was increasingly reserved for more formal events as the decade progressed. In the early 1860s, it featured a long, oversized cut with wide lapels and puffed sleeves. However, by the late 1860s, it had evolved to a slimmer fit with narrower sleeves and lapels. frock coats could be single or double-breasted and were often worn open to show the vest beneath.

Sack Coats

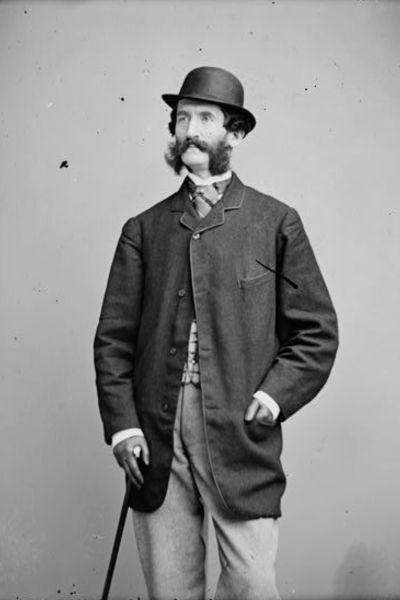

The sack coat gained popularity for informal daywear during this period. Distinguished by its lack of waist seam and shorter length, it was initially cut boxy and oversized in the early 1860s. The sack coat often featured a higher buttoning neckline and rounded hem at the front, foreshadowing the styles that would become prevalent in the following decade.

Cutaway Coats

Between the sack jacket and frock coat in formality was the cutaway (or "morning") coat, which became popular for business attire. It featured a waist seam and sloping "cutaway" opening, evolving from a less dramatic cutaway and more rounded hemline in the early 1860s to a more pronounced slope by the end of the decade. Later cutaways were often single-breasted with just one button for closure.

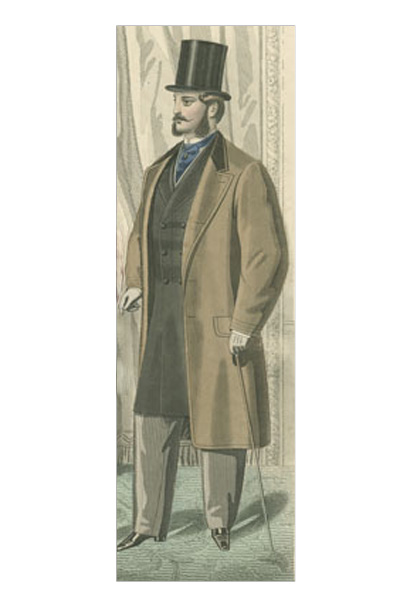

Overcoats

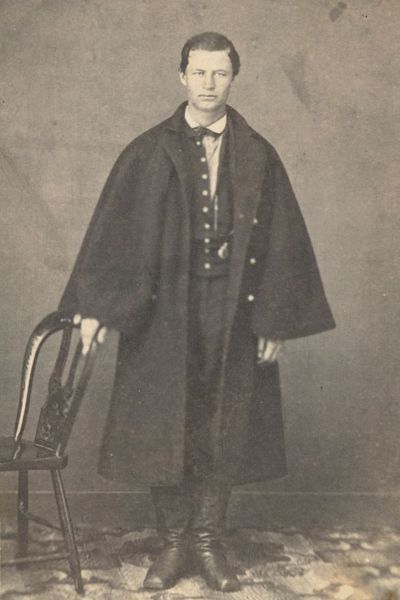

Overcoats, or "top frocks," became increasingly accessible in the 1860s due to advancements in ready-to-wear production. The Chesterfield, a knee-length coat without a waist seam, gained popularity for its versatile, formal appearance. It often featured a velvet collar and was suitable for both day and evening wear.

The Inverness coat, inspired by Scottish highland dress, was distinguished by its cape-like sleeves, providing both warmth and ease of movement.

The Ulster, a long, heavy overcoat, typically included a cape and belt, offering maximum protection against harsh weather. These styles, often adorned with capes or hoods, reflected the era's emphasis on practical yet fashionable outerwear, catering to various social occasions and climate needs.

Smoking Jackets / Robes

The smoking or breakfast jacket, considered "among the minor comforts of a gentleman," was popular for casual wear at home. These could be luxurious, made of velvet or quilted silk with contrasting lining, or simpler, made from contrasting colors of flannel, usually with braid trim and frog closures.

Sporting Jackets

As the 1860s progressed, two notable jacket styles gained prominence in men's fashion. The Norfolk jacket emerged as a favored option for shooting and country pursuits. This single-breasted jacket was characterized by its loose fit, belted waist, and distinctive box pleats on the back and chest. Often made from tweed or other durable fabrics, the Norfolk jacket included large patch pockets, making it both stylish and functional for outdoor activities. Its popularity among the upper classes for country wear helped establish it as a quintessential element of the British country gentleman's wardrobe.

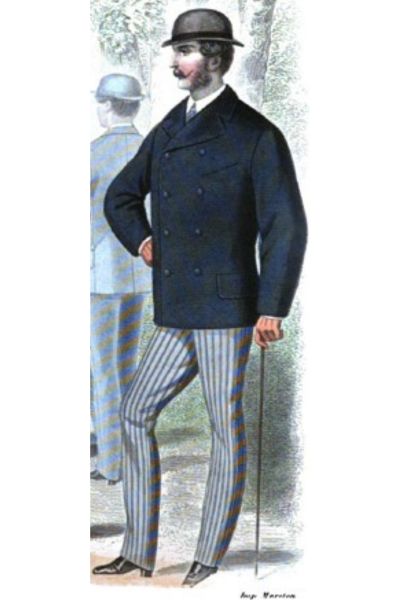

The Reefer jacket, a fashionable short, hip-length coat, also grew in popularity. Originally derived from naval uniforms, this double-breasted jacket featured a row of brass buttons on each side and was typically made from sturdy wool. Its practical design and smart appearance made it a versatile choice for both casual and semi-formal occasions.

Trousers

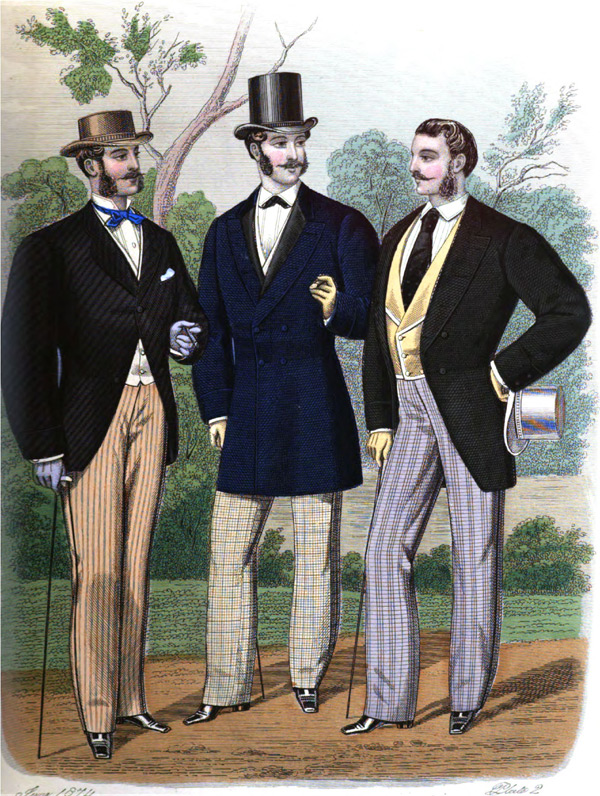

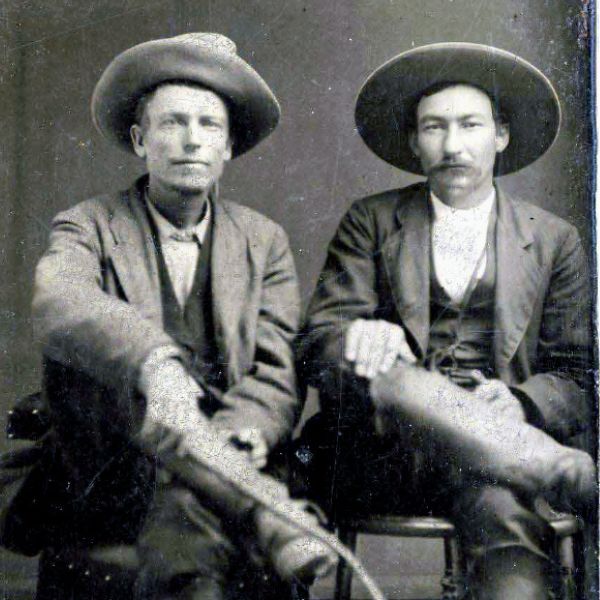

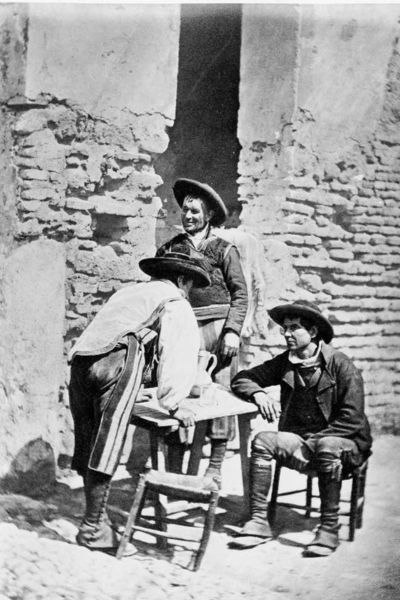

Trousers in the early to mid-1860s were cut loose with wide pant legs and no pleats, tapering slightly towards the ankle. They could be light or dark, matching or contrasting with the jacket, and stripes and bold checks were sometimes seen, especially in fashion plates. Trousers were almost always held in place by suspenders. As the decade progressed, trousers were cut slimmer, reflecting the changing overall silhouette

The 1860s also saw the introduction of knickerbockers, loose knee-length breeches worn for sports.

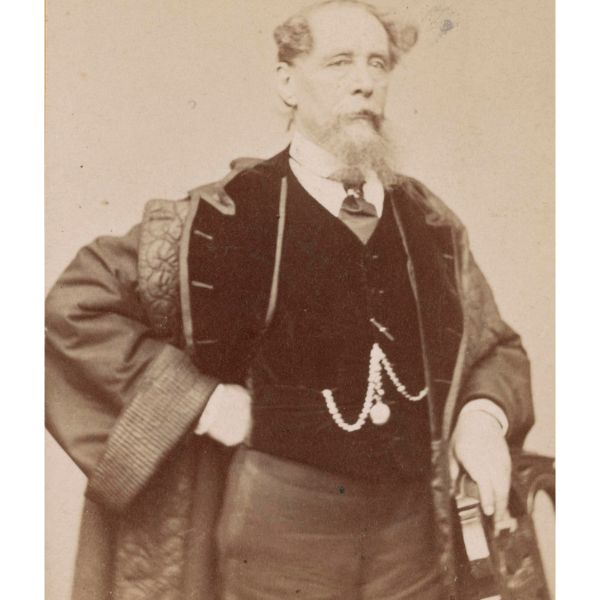

Vests

Vests, commonly called waistcoats, remained a staple of the male wardrobe for all classes. In the 1860s, they were more often single-breasted and featured a collar, most fashionably a shawl or rolled collar. Vest necklines began buttoning higher on the chest, especially later in the decade, revealing less of the shirt underneath. While vests often matched the jacket and pants in understated hues, they could also be seen in opulent damasks and rich jacquards in the fashionable vivid hues of the era.

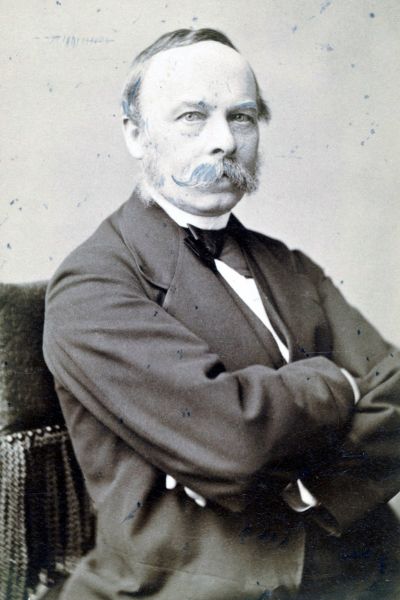

Shirts and Neckwear

Most shirts were white and plainer in the 1860s than in previous decades, although stripes and plaids were still seen. Shirts continued to be in the pullover style with a partial front placket. Most were made without collars or cuffs; a gentleman would have several sets of each, which could be washed and starched separately from the shirt and buttoned on. In the 1860s, collars were worn low on the neck and often turned down. Retired dress shirts were often worn collarless as work shirts.

The most fashionable neckwear of the decade was the narrow dark colored tie, worn fastened in the front with a knot or a bow.

However, taller stocks and wide neckcloths could still be seen worn in the 1860s, particularly by older gentlemen or for more formal occasions.

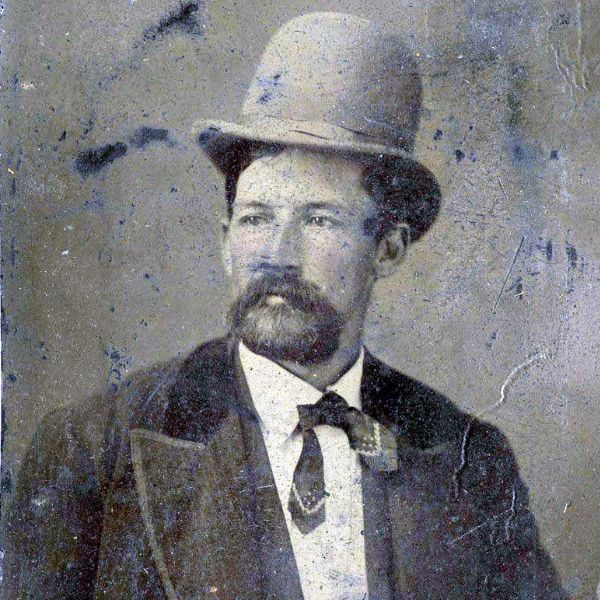

Hats

Hats remained an indispensable part of a man's wardrobe. Tall "stovepipe" silk black top hats continued to be the standard choice for day and evening occasions, worn with all styles of coat. However, the hard felt, dome-crowned derby/bowler hat became the fashionable and more youthful choice for pairing with a sack suit. Towards the end of the decade, it was increasingly seen chosen in place of a top hat for informal daywear. Straw boaters could also be seen worn in the 1860s for summer leisure.

In 1865 hatmaker John B. Stetson invented the Boss of the Plains hat, wide brimmed and made of strong dense felt, which found much favor, especially amongst ranchmen and settlers of the Old West.

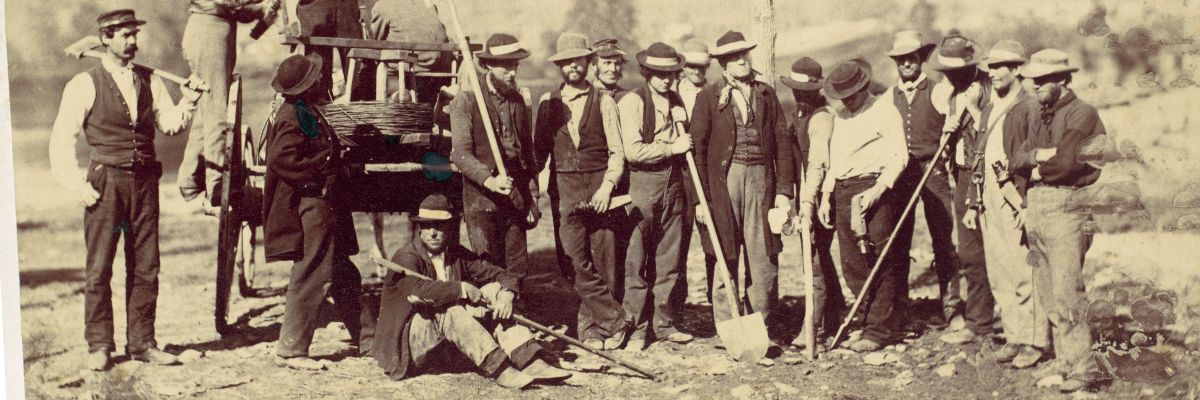

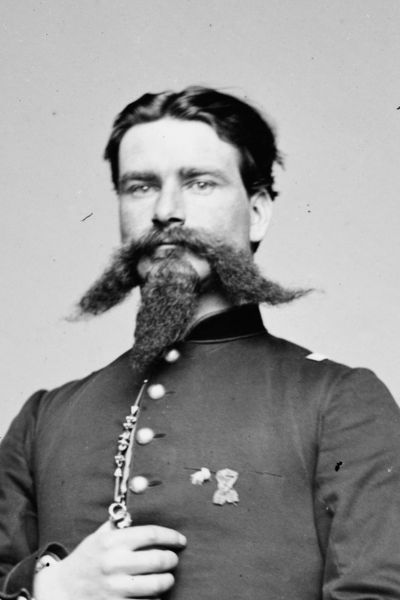

For work, and war, the soft felt wide-awake hat is seen throughout photographs in many shapes, and the military "kepi" was worn as a work hat for many years after the end of the civil war.

Footwear

Footwear in the 1860s was dominated by boots, most frequently seen in black or brown leather, laced-up or buttoned at the side. Tall boots with square toes were often seen during this period.

Shoes were not common except for sports such as tennis or cricket. Spatterdashers, or Spats, were worn to keep mud and muck off a gentleman's footwear, but were sometimes a fashion statement in colorful or unique fabrics.

Hair and Accessories

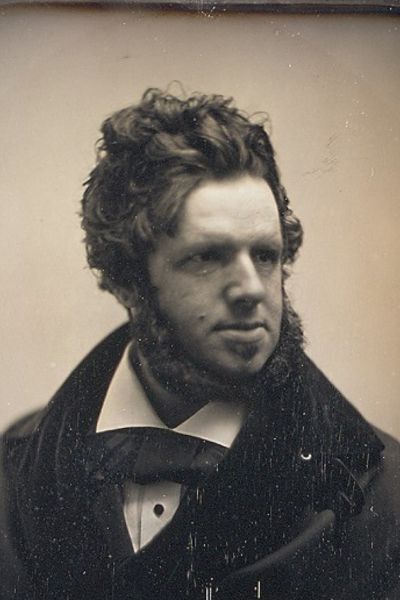

Men's hairstyles in the 1860s were typically cut at ear level and parted to one side, often with a wave. Sideburns were prevalent, sometimes short, sometimes long "muttonchops" or "Dundreary whiskers."

Named for Queen Victoria's husband, Prince Albert, pocket watch chains were popular accessories and seen draped as a single or double chain.

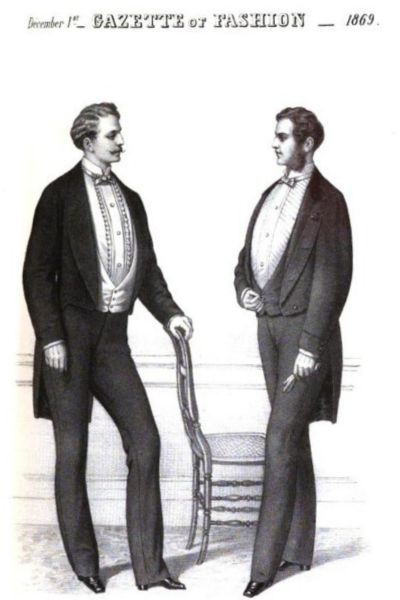

Evening Wear

Evening wear saw the tailcoat, once the height of fashion day and night, become an item for formal evening wear only. It was worn with a matching vest and trousers, and a white shirt with a stiffly starched front decorated in embroidery, fine pleats, tucks, or ruffles.

A wide cravat of light-colored silk or a white tie worn in a bow completed the ensemble. A silk top hat, especially the Gibus collapsible opera top hat, was the finishing touch. Towards the end of the decade, a velvet or silk shawl collar became fashionable on the tailcoat.